The word’s oceans are filled with creatures of all kinds – some harmless, some very dangerous to humans and other species. Sharks get a bad rap, but there’s plenty of other living being underwater you probably should be scared of more. Looks can be deceiving, indeed. Venomous animals are often alluring creatures you may be tempted to approach or even handle. Let’s take a look at some of the most venomous marine animals in the world and what makes them so dangerous.

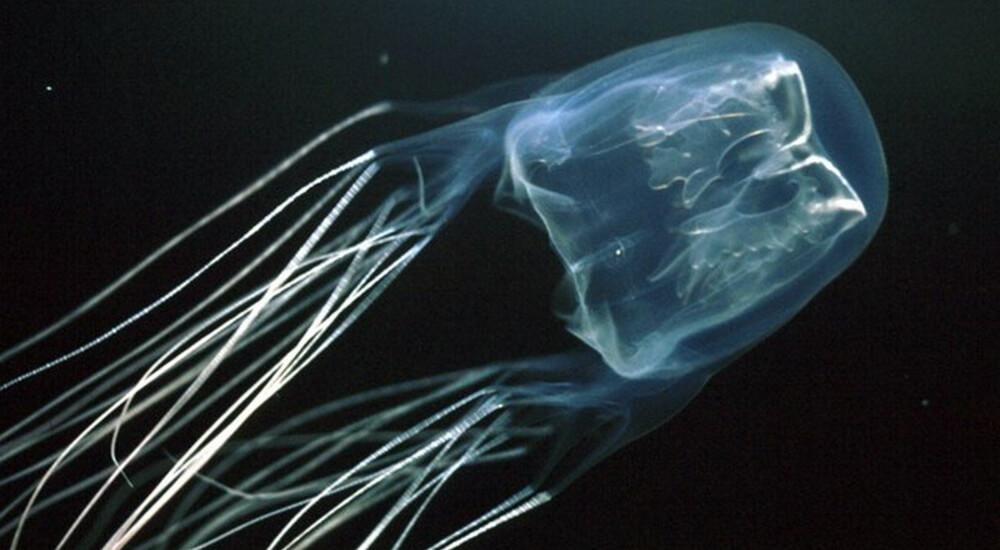

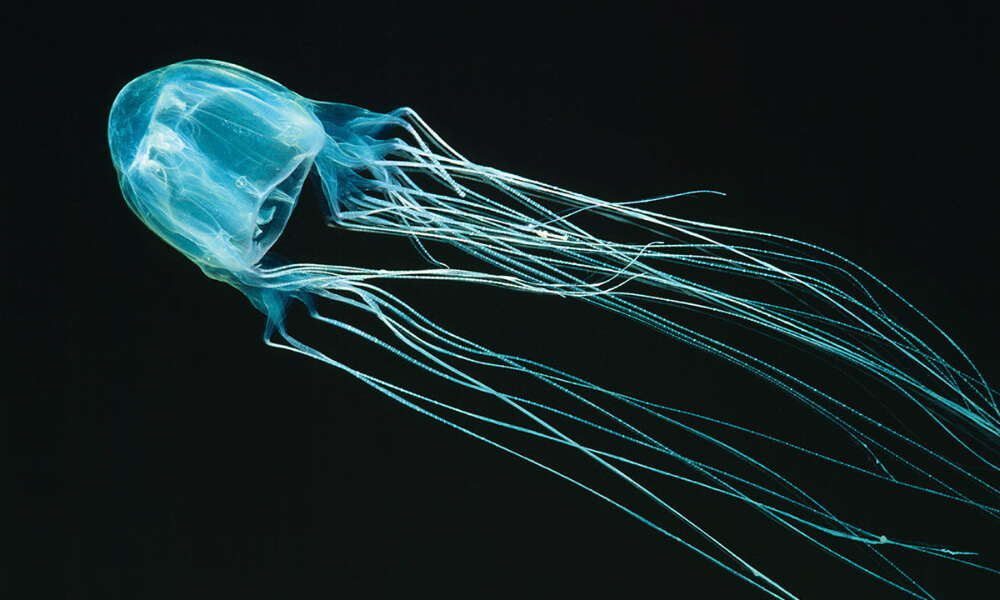

Box Jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri)

This may come as a surprise to many, but the most venomous marine animal in the world is not some menacing-looking creature that lurks in the deep ocean, but a beautiful jellyfish that lives in the shallow waters of the Indo-Pacific. Native to Australia, Chironex fleckeri is a species of extremely venomous box jellyfish found in the coastal waters of northern Australia as well as New Guinea, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Humans are frequently stung by this species off the coast of Queensland.

The Australian box jellyfish have up to 15 tentacles that can reach up to three meters in length. The tentacles are covered in cnidocytes, specialized cells containing nematocysts loaded with poison. When potential prey or predators stimulate these cnidocytes, water rushes into the nematocysts, exerting high pressure which in turn opens the nematocysts’ operculums, releasing the deadly venom.

The venom attacks the nerves, blood, and heart of the prey or predator. People and animals stung with Chironex fleckeri’s poison may experience intense pain, respiratory distress, paralysis, cardiac arrest, and even death, all within a few minutes after being stung. There have been at least 80 deaths caused by box jellyfish in Australia since 1883, but many injuries and deaths go unreported, so it is not a risk to be taken lightly. Nonetheless, most encounters result in mild envenomation.

An intravenous box jellyfish antivenom can be given to patients who exhibit life-threatening envenoming. Researchers are also working on developing a topical application in spray or cream form to alleviate pain and stop necrosis and skin scarring.

Blue-ringed Octopus (Hapalochlaena)

Blue-ringed octopuses are four highly venomous species of octopus that live in tide pools and shallow rocky reefs throughout the western Pacific and Indian oceans. Ironically for their small size and adorable appearance, are the deadliest cephalopods in the world. In fact, the venom of the blue-ringed octopuses is more potent than any venom found in land animals. Despite this, only three deaths caused by the blue-ringed octopus have ever been reported so far.

Recognizable by the blue and black rings that appear on its body when the animal feels threatened, the blue-ringed octopus possesses a venomous neurotoxin called tetrodotoxin, which is released through the animal’s salivary glands. Tetrodotoxin is 1,000 times more deadly than cyanide. The tiny amount of venom the little octopus carries can mean certain death for more than 20 people or can leave a human paralyzed for up to 24 hours after initial contact.

The bite itself is painless and victims may not realize they’ve been bitten until it is too late. Symptoms of envenomation include nausea, vision loss, loss of motor skills, loss of sense, and respiratory arrest. Unfortunately, there is no known antidote for the bite of the blue-ringed octopus and the only treatment is ongoing heart massage and artificial respiration. It is crucial that first aid procedures are started quickly to ensure the victim’s chance of survival.

Stonefish (Synanceia)

A close relative to the scorpionfish, stonefish is the world’s most venomous fish. Synanceia members are primarily marine and live in the coastal regions of the Indo-Pacific, though some species can be found in rivers. Stonefish usually lie motionless, buried in the substrate, and perfectly camouflaged against their surroundings, whether that’s coral, rubble, rocky reef, or aquatic plants. Although they don’t go out of their way to attack humans, they are difficult to spot and accidents can happen.

Stonefish have 13 sharp spines lining their back. At the base of each spine, there are two glands that release venom under pressure. The venom produced by these fish is some of the most potent in the world and is fatal to humans. When disturbed, the fish erects its spines while maintaining its position on the seafloor. Stonefish use venom only as a defense mechanism and never for hunting.

Those unlucky enough to come into contact with a stonefish will feel excruciating pain and swelling that may last for many days. Muscular paralysis, breathing difficulties, tissue necrosis, and sometimes heart failure and death can ensue. To prevent the worst from happening, an intravenous stonefish anti-venom was created in the 1950s. In the event of a sting, the victim should seek immediate medical attention.

Portuguese Man o’ War (Physalia physalis)

Often mistaken for a jellyfish, the Portuguese man o’ war is actually a siphonophore, an animal made up of gelatinous colonial animals of the phylum Cnidaria whose different members (zooids) work in unison to function like an individual animal. The name man o’ war most likely comes from an 18th-century sailing warship. The colonies spend a lot of time at the surface of the water, and when the gas bladder is expanded, it resembles a sailboat.

Man o’ wars are found in large groups, sometimes over 1,000 or more individuals, floating in warm waters throughout the world’s oceans. Since these siphonophores have no independent means of propulsion, they either drift on the currents or catch the wind with their aerial roots, called pneumatophores.

The zooids responsible for catching prey are called dactylozooids, which are tentacular mouthless zooids. The tentacles reach up to 50 meters in length and have numerous venomous microscopic nematocysts that deliver venom capable of paralyzing and killing large fish and crustaceans. For humans, the odds of being killed by the man o’ war’s sting are slim, but it does pack a painful punch and causes welts on exposed skin. The allergic reaction to the siphonophore’s venom can also affect a person’s breathing, which may lead to drowning. Learn about the preventive and first aid measures to keep yourself safe.

Cone Snail (Conus)

The genus Conus consists of over 600 species of cone snails in one big family – the Conidae. These gastropod mollusks are found in warm and tropical seas and oceans worldwide, reaching the greatest diversity in the western Indo-Pacific. Cone snails are some of the most venomous marine animals in the world and all species within the genus Conus secrete toxins.

Cone snails use a venom-filled radula tooth as a harpoon-like structure for predation. Once the nose the cone snail senses prey nearby, it deploys a long flexible tube called a proboscis from its mouth towards the prey. Cone snail venom is a complex mixture of compounds that cause paralysis through multiple neuromuscular blocking steps. The venoms are mainly peptides that vary between species. Researchers estimate that each animal harbors over 100,000 different bioactive compounds within their venom.

The sting of many of the smallest cone snail species may be no worse than that of a bee sting, but in the case of a few of the larger species, it can sometimes have fatal consequences. Symptoms of cone snail envenomation include intense pain, tingling, muscle paralysis, respiratory paralysis, and blurred/doubled vision. According to a 2016 paper, in the last 30 years, members of the genus Conus have claimed the lives of more than 35 people worldwide.

The intricate color patterns of cones have made them popular collectible seashells. Unfortunately, not even diving gloves offer enough protection against the animals’ sting. Contact should be avoided, even if the shell looks empty because it may still have a living animal inside. There is no anti-venom for cone snails. Victims should seek urgent hospital-based therapy; intensive care hospitalization may be required.

Flower Urchin (Toxopneustes pileolus)

The flower urchin is a widespread species of sea urchin from the Indo-West Pacific. It inhabits seagrass beds, coral reefs, and rocky or sandy seafloor. Toxopneustes pileolus are beautiful creatures, spectacularly colored with very short spines and long petal-shaped pedicellariae, which give rise to their common name – flower sea urchins.

As beautiful as flower sea urchins are, as dangerous they can be. As a matter of fact, Toxopneustes pileolus are the most venomous of sea urchins and unlike others, they do not deliver the venom through their spines. The envenomation mechanism involves the globiferous pedicellariae which are usually expanded into cup-like shapes. When disturbed, the pedicellariae will immediately snap shut and release venom.

Sea urchin stings are immediately painful, and the area may become red and swollen. The puncture wounds on the skin can become infected if not treated immediately. The flower urchin’s venom can also cause nausea, vomiting, weakness, tingling, abdominal pain, fainting, hypotension, and respiratory distress. Strangely enough, there are very few recent accounts of how toxic or potent the Toxopneustes pileolus’ poison can be, but some accounts have stated that people have drowned following flower urchin stings. But in absence of official reports, we dare not throw any more shade at this beautiful creature.

Dubois’ sea snake (Aipysurus duboisii)

Dubois’ sea snake is not only one of the most venomous marine animals but the most venomous sea snake in the world and the third most poisonous of all snakes. This deadly creature is found from Papua New Guinea to New Caledonia and the northern, eastern, and western coasts of Australia. The Aipysurus duboisii is most often observed in shallow water at depths of only 3-4 meters but can live at depths of up to 80 meters.

The snake’s venom contains strong neurotoxins (postsynaptic neurotoxins) that may cause paralysis and death. Individuals may be bitten under self-defense when the snake is threatened or handled, but this species is reportedly only mildly aggressive. Its fangs are also very tiny (about 1.8 mm long) and may not penetrate some wetsuits. Nonetheless, its bite can be life-threatening.

Coral reef divers have the highest risk for being bitten and in some cases, fang marks may not even be visible. Even though envenomation is rare, the snake possesses fast-acting neurotoxins that can cause rapid muscle breakdown and neurological symptoms. In most cases, however, the venom is not known to severely affect humans. Early administration of antivenom is the mainstay of treatment. The prognosis of Aipysurus duboisii’s bite with immediate therapy is usually good.

Hopefully, this list of the most venomous marine animals hasn’t killed your eagerness to dive but has made you more aware of the possible dangers that you need to watch out for more. The chances of an unprovoked attack are slim but be sure to keep your hands to yourself as tempting as it may be to touch some of the creatures you see underwater. Keep a safe distance and stay safe!

One thought on “7 Most Venomous Marine Animals in the World”