Deep in the waters of Howe Sound, British Columbia, resides one of the oldest life forms on Earth – the glass sponge. It wasn’t until the mid-1980s when researchers discovered these “living dinosaurs,” previously believed to have gone extinct during the Jurassic period. Here are some interesting facts about these ancient reef-forming organisms that grow on top of the skeletons of previous generations.

What Are Glass Sponges?

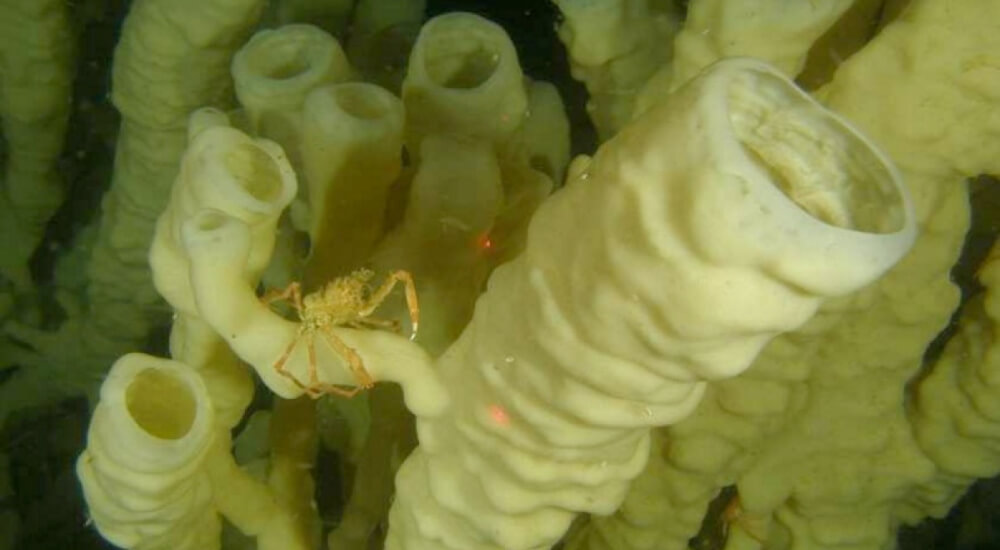

Hexactinellid sponges are one of four classes of sponges in the Phylum Porifera. These cup-shaped animals typically range from 10 to 30 centimeters, or 3.9 to 11.8 inches, in height, but some grow to be quite large. Coloration in most is pale. Hexactinellid sponges resemble other types of sponges, such as syconoid sponges, but their internal structure is very different.

Upon close examination, Hexactinellid sponges can be distinguished from other sponges due to their internal skeleton made up of overlapping spicules of silica, which earned them the name of “glass sponges.” The siliceous spicules are typically composed of three perpendicular rays and are often fused, giving the glass sponges a structural rigidity atypical of any other sponge.

Hexactinellid sponges are sessile filter feeders, consuming macroscopic detritus material for the large part, but also bacteria, cellular material, and nonliving particles. These animals seem to lack selective control over the food that passes through them, so any food small enough to penetrate their syncytium is ingested. Furthermore, they have also been found to lack control over how much water passes through them.

Although they are found in all of the world’s oceans, glass sponges are relatively uncommon and the only place where they are known to form reefs is on the western Canadian continental shelf. Sponge reefs require specific conditions, which may explain their rarity. Hexactinellid sponges can only live on hard substrates and do not anchor to muddy substrates or sandy seabeds.

The Discovery of Glass Sponge Reefs

For decades, scientists knew of glass sponge reefs only as Mesozoic-era fossils that existed some 160 million years ago. These reefs once carpeted the Tethys Ocean, which was an ancient ocean located between the ancient continents of Gondwana and Laurasia. As such, it came as quite of a surprise when in the 1980s, a team of oceanographers on a seafloor mapping expedition discovered some strange mounds over huge areas of the seafloor that should have been completely flat.

The first glass sponge reefs were discovered between 1984 and 1988 by the Geological Survey of Canada during geophysical surveys in the depths of the Queen Charlotte Sound and Hecate Strait off British Columbia. The researchers discovered that the sponges were not only alive but had formed extensive reefs. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the reefs started forming about 9,000 years ago.

Further explorations revealed that the reefs spanned some 700 square kilometers, or 280 square miles, of the ocean floor. A decade later, more reefs were discovered in the Georgia Strait off the southern British Columbia. Even after the discoveries of the 1980s and 1990s, researchers continued to find new colonies. In 2007, a geologist from the University of Washington discovered large colonies of glass sponges thriving on the seafloor west of Grays Harbor, Washington. Nonetheless, to this day, the Pacific Northwest is the only known area with living such reefs in the world.

The Importance of Glass Sponge Reefs

Glass sponge reefs are very important in the filtration of the ocean. According to research, glass sponges filter bacteria from the water and excrete ammonium, thus acting as a fertilizer for the water column. It is estimated that one single sponge can filter up to 9,000 liters of water a day! According to the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, a single small reef can filter enough water to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool in less than a minute.

Glass sponges also provide refuge and habitat for numerous marine animals and function as a nursery for rockfish and a source of food for other different species of fish and invertebrates. The cloud sponge (Aphrocallistes vastus), one of the most important reef-forming glass sponges, has been found to accommodate a wide variety of organisms, including hairy-spined crabs, tiny squat lobsters, shrimp, and polychaete worms inside its osculum and on its surface. Epifauna observed adjacent to the sponge reefs includes soft corals, sea whips, anemones, and large individual sponges.

Vulnerability

Unfortunately, these unique and vital ecosystems are as fragile as glass due to their internal skeleton made of silica. They are most vulnerable to damage caused by a form of commercial fishing known as bottom trawling, where a large net is dragged across the ocean floor. While not as harmful, hook fishing, line fishing, and crustacean trapping are also damaging to the reef. These impacts result in potentially long-term consequences, as sponge larvae require the siliceous skeletons of past generations as substrate. Without the hard substrate to anchor to, the new sponges cannot regrow the broken parts of the reef. The broken sponge reefs are estimated to take up to 200 years to recover from damage.

According to research by the University of British Columbia, climate change is another threat to the glass sponge reefs. For the study, researchers harvested one of the main types of reef-building glass sponges and conducted a long-term lab experiment where the sponges’ resilience was tested by placing them in warmer and more acidic waters that mimicked future projected changes to the ocean conditions. Warming ocean temperatures and acidification have been found to drastically reduce the skeletal strength of the sponges as well as their filter-feeding capacity. The findings indicate that the damage caused by climate change could have irreversible impacts not only on the sprawling glass sponge reefs but also on their associated marine life.

Scuba Diving Glass Sponge Reefs

As far as everyone knows, Howe Sound – North America’s southernmost fjord, is the only place in the world where glass sponge reefs are found in water as shallow as 40 meters, or 125 feet. Other bioherms are spread across the tops of seamounts in deeper waters of 80-100 meters, or 250-330 feet, that could be explored by technical mixed gas divers.

The diving conditions at Howe Sound are harsh, with depth, no visible daylight from the surface, poor visibility, strong tidal exchanges throughout the year, and unpredictable weather conditions posing multiple challenges even for the most experienced divers. Although difficult, these rewarding dives are deemed unforgettable. In the murky darkness, glass sponge reefs grow as high as 20 meters, or 66 feet.

Those who wish to know more about the possibility of diving these unique reefs can get in touch with the Deep Glass Sponge Dive Team or the local dive operators such as Sea Dragon Charters.

How long the glass sponge reefs remain open for recreational diving depends on how well divers protect these fragile bioherms. Divers need to possess excellent buoyancy control as even the slightest fin kick can cause serious damage to these ancient animals.

Final Thoughts

Glass sponge reefs are an integral part of the ocean ecosystem of British Columbia. In 2017, Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound Glass Sponge Reefs have been designated as a Marine Protected Area to help conserve these truly unique reefs. As new research proved that current restrictions are not enough to protect the glass sponges, scientific communities continue to work on implementing new protective measures so that these exceptional ecosystems can thrive for many years to come.

Photo credits: Fisheries and Oceans Canada